What every developer must know about TLS

Transport Layer Security (TLS) or, as many still call it: SSL, is a cornerstone technology of the internet. It enables internet banking, many b2b applications and secure communications with your doctor. With the advent of free certificates from Let’s Encrypt, there are no more excuses for websites not to support it.

As a result of the increasing adoption of HTTPS, the secure version of HTTP (or HTTP over TLS). Many developers are forced to learn how to configure their web servers for TLS. Many of them don’t quite understand how it all works and stumble through tutorials, settings, certificate files and checkboxes hoping to get it to work. When it finally does, they leave it all alone until it inevitably breaks and the process of trial and error begins anew.

To prevent too many people from making the same mistakes over and over again, I decided to write this article. Much of this is old news to many people but it’s my hope that there is a nugget of missed understanding here and there that will be useful. This article is a high-level overview and in no way attempts to convey technical details about the underlying protocols.

TLS 101

TLS is a communications protocol with two goals: authentication and privacy. The goal is to know who you’re talking to and to make sure nobody else can listen in on the conversation. To understand how TLS achieves these goals, we first have to go over some basics.

Privacy

When two parties want to exchange information without anyone finding out what that information is, that information can be encoded in a way that can be decyphered by the communicating parties but not by anyone else. An uncountable number of schemes have been devised for achieving this, ranging from the simple Ceasar Cipher to full blown quantum cryptography. Most of these schemes are not (yet) relevant to TLS, however, so we’ll limit ourselves to the RSA system.

In the RSA cryptography system, the two parties (traditionally called Alice and Bob) that want to communicate first both create something called a key pair, this key pair consists of a public key and a private key (both are essentially very large numbers). The specifics are not important here, but suffice it to say that when Alice encrypts a message with Bob’s public key, it can only be decrypted by Bob’s private key. Conversely when Bob wants to send a message to Alice, he needs to encrypt it with her public key so Alice can later decrypt it with her private key.

Aside from encrypting messages, RSA can also be used to sign messages. A message signature proves who wrote the signed message and that the messages has not been altered after having been signed. In order to sign a message, Alice will compute a hash of the message and encrypt that hash with her private key. Anyone that has Alice’s public key can then verify the signature and know the message was signed by Alice and has not been modified.

To learn more about RSA and other asymmetric crypto systems, see Public-key cryptography on Wikipedia.

Authentication

Privacy by itself is not enough for secure communications. An eavesdropper may not be able to listen in on the connection after it’s been established, but it’s still perfectly possible for a Man in the Middle (MITM) to intercept the connection and establish key pairs with both sides of the connection. The MITM is then able to decrypt all traffic from Alice and re-encrypt it before sending it off to Bob. Alice and Bob are none the wiser without the second important property of TLS: authentication.

In TLS, authentication is achieved by using certificates (see X.509). A certificate is simply a public key bundled with some information about its owner that is signed by a trusted third party (a certificate authority). Think of it like a passport, a passport can be used to prove someone’s identity because it was issued by a trusted third party (that person’s government).

Basics of a TLS connection

A TLS connection begins when a client (i.e. a web browser) sends a Client Hello message to a server (a web server). This message contains some basic information about the connection the client wants to establish: the protocol versions supported, a list of supported encryption protocols, hashing algorithms, etc. It contains everything the server could possibly want to know about what the client supports so it’s free to choose the most secure combination of algorithms both client and server support.

After receiving the Client Hello, the server will reply with its own Server Hello message that informs the client of the chosen encryption- and hashing algorithms, various parameters and the all important Server Certificate.

The server certificate contains the server’s public key and information about the server that owns that key (such as the company that owns it, etc). Most importantly, it contains the server’s name (called the “Common Name” or CN). Any TLS client must compare the name in the certificate with the name they were trying to connect to and reject the connection if they don’t match to prevent man in the middle attacks.

After the Server Hello and associated messages, the client must now decide whether to trust the certificate the server has offered or abort the connection, more about that later. The client can also send a certificate of its own in a Client Certificate message. This is used for Mutual authentication, which is more rare and outside the scope of this article.

Chain of trust

How does a TLS client know whether to trust the certificate a server has offered? As you will remember, the certificate contains a public key and some information about the owner of that key, such as its name. In the case of a web server this name will be the domain name of the server, something like “somecompany.com”. The certificate can also contain some alternative names, such as “www.somecompany.com" so the certificate can be used for multiple domain names.

A certificate also contains validity dates, an issuer name and a signature from that issuer. The certificate for “somecompany.com” therefore looks something like this:

| Item | Example |

|---|---|

| Name(s) | somecompany.com, www.somecompany.com |

| Valid from | December 1, 2017 |

| Valid until | December 1, 2020 |

| Public key | a very large number |

| Issuer | TrustUs Inc. Certificate Authority |

| Signature | — signed by TrustUs Inc. — |

In order for a client to trust a certificate it must be valid at the time of connection; it must belong to the server the client is trying to connect to and; it must have been signed by a certificate authority the client trusts. Every TLS client is configured with a trust store, a list of certificate authorities that it trusts. Only certificates signed by a trusted authority will be accepted.

For web browsers, the trust store can be built in to the operating system (Internet Explorer, Google Chrome or Safari) or the browser vendor can provide its own (Firefox). Typically, there exists some management interface to add and remove certificates manually (Keychain Access on the Mac, the Certificate Manager SMC snap-in) on Windows but this store is most often maintained by the operating system or browser vendor. For non-web browser applications, the trust store is often configured separately. However the setup for any particular operating system or application, there is always a trust store containing the trusted certification authorities.

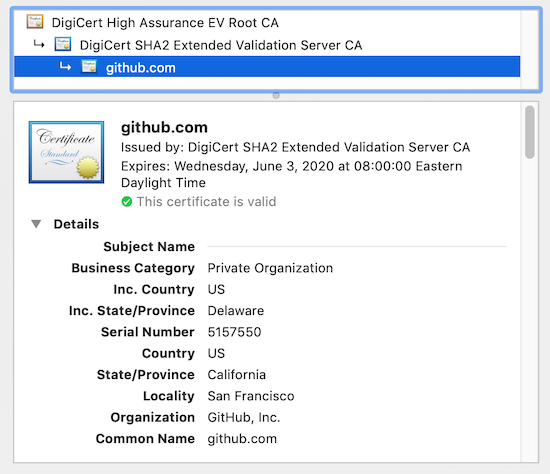

Let’s examine a real world certificate. For illustration purposes, we’ll use the certificate for github.com:

This certificate’s chain of trust is a little more complicated than the above description. The certificate for “github.com” was signed by the issuer “DigiCert SHA2 Extended Validation CA”, which in turn is signed by the issuer “DigiCert High Assurance EV Root CA”. In many situations, certificate authorities use “intermediate” certificates. These intermediate certificates often have shorter validity dates than their main certificate and are only used for signing certain types of certificates (in this case only for Extended Validation certificates, a type of certificate with strict validation of the company it represents).

When connecting to github.com, the server will send us both its own certificate and also the above intermediate certificate. It may send more, enough to form a “chain of trust” all the way up to a certificate that is included in the client’s trust store. In order for a client to check the validity of the server’s certificate it has to be able to check the validity of all certificates leading up to a trusted root certificate (the ones in its trust store).

When connecting to github.com, a web browser will:

- check whether the “github.com“ certificate’s signature is valid;

- move up the chain to the intermediate certificate (in this case “DigiCert SHA2 Extended Validation CA“), and check its validity dates and signature

- lastly, it encounters the certificate “DigiCert High Assurance EV Root CA“. This root certificate is explicitly trusted because it’s included in the browser’s trust store.

Configuring your server

In order for a server to use TLS, it needs two things: a certificate and the corresponding private key. How to obtain these depends on your certificate issuer, there are two common approaches:

- The certificate issuer generates a key and certificate. These are offered for download to the server and can be installed directly. This process is convenient, but less secure than the alternative.

- The server administrator generates a key pair themselves and sends the issuer a certificate request. The issuer converts this request into a certificate and offers it for download. This approach is more secure since nobody but the server administrator ever gets to see the private key.

Once the certificate and private key are both available, they can be entered into the server configuration. In many cases, the certificate issuer will also provide a “certificate chain” file or a separate intermediate certificate for download. The server configuration must contain all certificates required to link the server certificate to a well-known trusted root.

Depending on your server software, you may have to combine the server certificate and any intermediates into a single file or they can be configured as separate files. For more information on how to configure some often used server software, refer to the following links:

Apache 2.4 | NGINX | Microsoft IIS 8 | Postfix | Qmail | Microsoft Exchange

Common issues

TLS Version Conflicts

Mismatched parameters

Useful commands

openssl x509 -in certificate.crt -text

Print out a certificate in human readable form. Append -noout to suppress the base64 form of the certificate.

openssl verify -CAfile bundle.crt certificate.crt

Verify a certificate chain using a set of certificates in bundle.crt (a file of concatenated, PEM formatted trusted certificates).

openssl s_client -connect domain1.com:443

Connect to a server and print out debug information (including the server’s certificate in base64 format). Append -showcerts to print any additional certificates the server may be sending as well. Use -servername to enable the SNI extension and specify the server name to send.

openssl x509 -in certificate.cer -inform der -out certificate.crt

Convert a certificate from DER format to PEM format.